Introduction

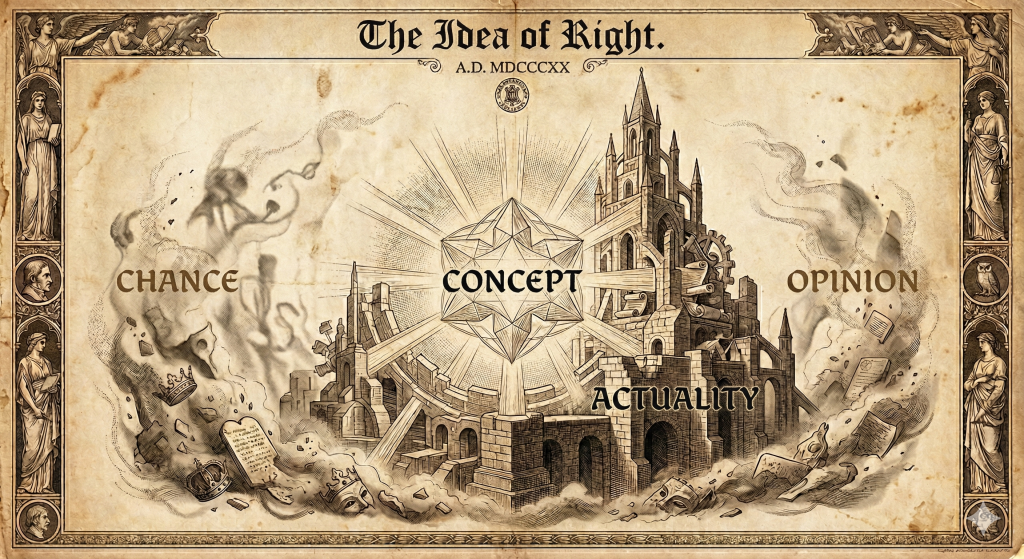

The philosophical science of right has as its object the Idea of Right, the Concept of Right and its actualization.

Philosophy has to do with Ideas, and therefore not with what are commonly called ‘mere concepts’; on the contrary, it demonstrates their one-sidedness and untruth. It further shows that the Concept alone (not what is often so-called, which is merely an abstract determination of the understanding) is what possesses actuality, and indeed in such a way that it gives this actuality to itself. Everything that is not this actuality, posited by the Concept itself, is transitory existence, external contingency, opinion, insubstantial appearance, untruth, delusion, etc. The configuration which the Concept gives to itself in its actualization is, for the cognition of the Concept itself, the other essential moment of the Idea, distinct from its form of being merely a Concept.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.