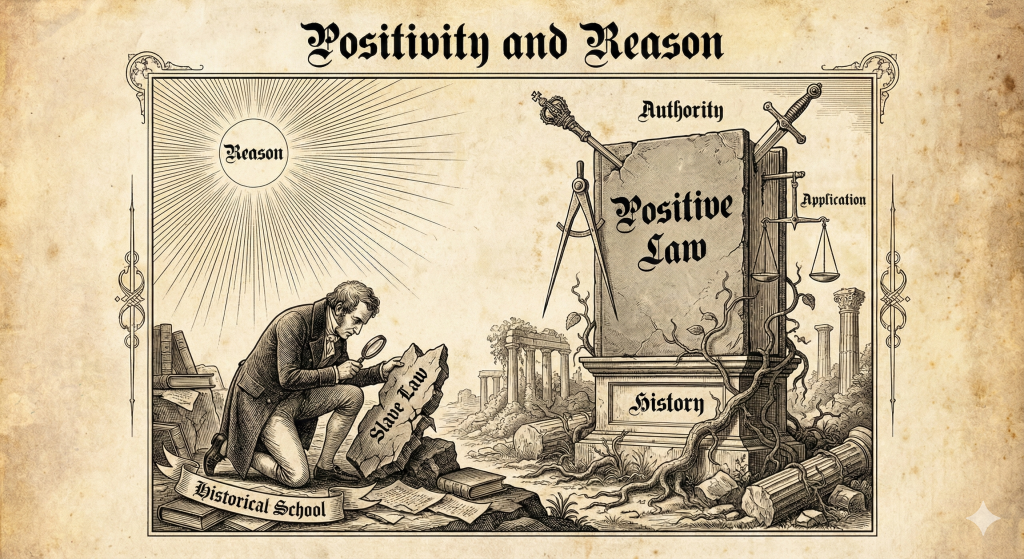

Right is positive in general a) through the form of having validity in a state; this statutory authority is the principle for the cognition of right, i.e., for the positive science of law. b) In terms of its content, this right receives a positive element: α) through the particular national character of a people, the stage of its historical development, and the interconnectedness of all those relations which are conditioned by natural necessity; β) through the determination required for the application of the universal Concept to the particular nature of objects and cases, which must be left to the discretion of the judge’s understanding; γ) through the final determinations required for making a decision in actuality.

When the feeling of the heart, inclination, and arbitrariness are set up in opposition to positive right and the laws, it cannot, at least, be philosophy that recognizes such authorities. – That violence and tyranny can be an element of positive right is accidental to it and does not concern its nature. It will be shown later, in §§ 211–214, where right must become positive. The determinations that will emerge there have been introduced here only to mark the limit of philosophical right and to eliminate at once any possible notion, or even demand, that a positive law code—i.e., such as a real state requires—should emerge from the systematic development of right. – That natural right or philosophical right is different from positive right should not be distorted into the view that they are opposed and in conflict with each other; the former stands in relation to the latter much as the Institutes stand to the Pandects. – With regard to the historical element in positive right, first mentioned in the paragraph, Montesquieu has given the true historical view, the genuinely philosophical standpoint, by considering legislation in general and its particular provisions not in an isolated and abstract way, but rather as a dependent moment of a totality, in connection with all the other determinations which constitute the character of a nation and an age; it is in this connection that they receive their true meaning and, with it, their justification. – The consideration of the emergence and development of legal provisions as they appear in time, this purely historical endeavor, as well as the cognition of their logical consistency as it proceeds from comparing them with already existing legal relations, has its merit and value in its own sphere and stands outside of any relation to the philosophical consideration, that is, insofar as the development from historical grounds is not confused with the development from the Concept, and the historical explanation and justification is not extended to the significance of a justification that is valid in and for itself. This distinction, which is very important and must be held to firmly, is at the same time very evident; a legal provision can be shown to be perfectly well-founded and consistent based on the circumstances and existing legal institutions, and yet be unjust and irrational in and for itself, like a host of the provisions of Roman private law which flowed with perfect consistency from such institutions as Roman paternal power and the Roman institution of marriage. But even if legal provisions are just and rational, it is one thing to demonstrate this of them, which can only truly be done through the Concept, and quite another to present the history of their emergence, the circumstances, cases, needs, and events which brought about their establishment. Such a demonstration and (pragmatic) cognition from nearer or more remote historical causes is often called explaining, or even better, comprehending, in the opinion that by this demonstration of the historical, everything, or rather the essential thing that is all that matters, has been done to comprehend the law or legal institution, whereas in fact the truly essential thing, the Concept of the matter, has not been mentioned at all. – Thus one is also accustomed to speak of Roman and Germanic legal concepts, of legal concepts as they are determined in this or that law code, whereas what is at issue here is nothing of Concepts, but only general legal determinations, propositions of the understanding, principles, laws, and the like. – By setting aside that distinction, one succeeds in shifting the standpoint and playing off the question of true justification into a justification from circumstances, a consistency from presuppositions which may in themselves be equally worthless, etc., and in general in substituting the relative for the absolute and external appearance for the nature of the matter. When historical justification confuses external emergence with emergence from the Concept, it unconsciously does the opposite of what it intends. If the emergence of an institution under its specific circumstances proves to be perfectly expedient and necessary, and the demand of the historical standpoint is thereby satisfied, then, if this is to pass for a general justification of the thing itself, the opposite rather follows: namely, that because such circumstances are no longer present, the institution has thereby lost its meaning and its right. 12) So, for example, if the merit of monasteries in cultivating and populating wastelands, in preserving scholarship through teaching and transcribing, etc., is put forward for their preservation, and this merit is regarded as the ground and determination for their continued existence, it follows rather from this very thing that under completely changed circumstances they have, at least in this respect, become superfluous and inexpedient. – Since the historical meaning, the historical demonstration and rendering comprehensible of the emergence, and the philosophical view likewise of the emergence and Concept of the thing, have their home in different spheres, they can for that reason maintain an indifferent posture towards one another. But since, even in science, they do not always maintain this peaceful posture, I will add something more concerning this contact, as it appears in Mr. [Gustav] Hugo’s Textbook on the History of Roman Law [1799], from which a further clarification of that manner of opposition can emerge. Mr. Hugo states there (5th edition [1818], § 53), ‘that Cicero praises the Twelve Tables, with a side-glance at the philosophers’, but ‘that the philosopher Favorinus treats them in exactly the same way as many a great philosopher has since treated positive right’. Mr. Hugo, in the same place, expresses the once-and-for-all definitive reply to such treatment in the reason he gives: ‘because Favorinus understood the Twelve Tables just as little as the philosophers understand positive right’. – As for the correction of the philosopher Favorinus by the legal scholar Sextus Caecilius in Gellius, Noctes Atticae, XX, 1 [22 f.], it expresses first of all the enduring and true principle of justification for what is, in its content, merely positive. “Non ignoras”, Caecilius says very well to Favorinus, “legum opportunitates et medelas pro temporum moribus et pro rerum publicarum generibus, ac pro utilitatum praesentium rationibus, proque vitiorum, quibus medendum est, fervoribus, mutari ac flecti, neque uno statu consistere, quin, ut facies coeli et maris, ita rerum atque fortunae tempestatibus varientur. Quid salubrius visum est rogatione illa Stolonis … , quid utilius plebiscito Voconio … , quid tam necessarium existimatum est … , quam lex Licinia … ? Omnia tamen haec obliterata et operta sunt civitatis opulentia …” 13) (You are not unaware that the expediency and remedies of laws are altered and bent according to the customs of the times and the types of constitutions, and according to the requirements of present utilities, and according to the fevers of the vices that must be cured; they do not persist in a single state, but, just as the face of the sky and the sea, they are changed by the tempests of affairs and of fortune. What seemed more wholesome than that rogation of Stolo… what more useful than the plebiscite of Voconius… what was deemed so necessary… as the Licinian law…? Yet all of these have been obliterated and buried by the opulence of the state…). These laws are positive insofar as they have their meaning and expediency in circumstances, and thus have only a historical value in general; for this reason they are also of a transitory nature. The wisdom of legislators and governments in what they have done for existing circumstances and established for the conditions of their time is a matter unto itself and belongs to the judgment of history, by which it will be recognized all the more deeply, the more such a judgment is supported by philosophical [handwritten note § 3 (b)] viewpoints. – But concerning the further justifications of the Twelve Tables against Favorinus, I wish to cite an example, because Caecilius in doing so employs the immortal deception of the method of the understanding and its reasoning: namely, to give a good reason for a bad thing and to believe to have justified it thereby. For the atrocious law which gave a creditor, after the prescribed period had elapsed, the right to kill the debtor or sell him as a slave, or even, if there were several creditors, to cut pieces from him and so divide him among themselves—and indeed in such a way that if one cut too much or too little, no legal claim should arise from it (a clause that Shakespeare’s Shylock, in The Merchant of Venice, would have benefited from and most gratefully accepted)—Caecilius adduces the good reason that trust and good faith would thereby be all the more secured, and that precisely because of the atrocity of the law, it was never supposed to be applied. In his thoughtlessness, he not only misses the reflection that precisely through this provision that very intention, the securing of trust and good faith, is nullified, but that he himself immediately thereafter cites an example of the law concerning false testimony failing in its effect because of its excessive punishment. – But what Mr. [handwritten note § 3 (c)] Hugo means by saying that Favorinus did not understand the law is impossible to see; any schoolboy is capable of understanding it, and the aforementioned Shylock would best of all have understood the cited clause, which was so advantageous for him; – by understanding, Mr. Hugo must mean only that cultivation of the understanding which is satisfied with a good reason for such a law. – A philosopher can, by the way, admit to another failure of understanding pointed out to Favorinus by Caecilius in the same passage without blushing, namely that iumentum, which according to the law was to be provided to a sick person to bring him to court as a witness—and not an arcera (covered litter)—was supposed to mean not only a horse but also a chariot or wagon. Caecilius could have drawn from this legal provision further proof of the excellence and precision of the ancient laws, namely that they went so far as to make a determination for bringing a sick witness to court that distinguished not only between a horse and a wagon, but between wagon and wagon, a covered and cushioned one, as Caecilius explains, and one that is not so comfortable. One would thus have the choice between the harshness of that law or the triviality of such provisions—but to declare the triviality of such things, and especially of the learned explanations thereof, would be one of the greatest offenses against this and other forms of erudition.

Mr. Hugo, however, in the cited textbook, also comes to speak of rationality with respect to Roman law; what struck me about this is the following. After he has said in the treatment of the period from the origin of the state up to the Twelve Tables, §§ 38 and 39, ‘that they (in Rome) had many needs and were compelled to work, for which they required draft and pack animals as helpers, such as we have, that the land was an alternation of hills and valleys and the city was on a hill, etc.’ – statements by which perhaps the sense of Montesquieu was supposed to have been fulfilled, though one will hardly find his spirit captured thereby – he then states in § 40, ‘that the legal condition was still very far from satisfying the highest demands of reason’ (quite right; Roman family law, slavery, etc., do not satisfy even very low demands of reason), but in the following periods Mr. Hugo forgets to indicate in which, and whether in any of them, Roman law did satisfy the highest demands of reason. However, concerning the classical jurists, in the period of the highest development of Roman law as a science, it is said in § 289, ‘that it has long been noted that the classical jurists were educated by philosophy’; but ‘few know (though through the many editions of Mr. Hugo’s textbook, several more now know it) that there is no kind of writer who so deserves to be placed alongside the mathematicians for their consistent deduction from principles, and, in a quite striking peculiarity of the development of concepts, alongside the modern creator of metaphysics, as precisely the Roman jurists: the latter is evidenced by the remarkable circumstance that nowhere do so many trichotomies occur as with the classical jurists and with Kant’. – That consistency praised by Leibniz is certainly an essential quality of the science of law, as of mathematics and every other science of the understanding; but this consistency of the understanding has as yet nothing to do with satisfying the demands of reason and with philosophical science. Besides, the inconsistency of the Roman jurists and praetors is to be regarded as one of their greatest virtues, through which they deviated from unjust and abominable institutions, but saw themselves compelled to invent cleverly empty verbal distinctions (like calling what was after all an inheritance a Bonorum possessio) and even a foolish evasion (and foolishness is also an inconsistency) in order to save the letter of the Tables, as through the fictio, ὑπόϰϱισις, that a filia (daughter) was a filius (son) (Heineccius, Antiquitatum Romanarum … liber I [Frankfurt 1771], tit. II, § 24). – It is comical, however, to see the classical jurists placed alongside Kant on account of a few trichotomous divisions—especially according to the examples cited there in note 5—and to see this called a development of concepts.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.