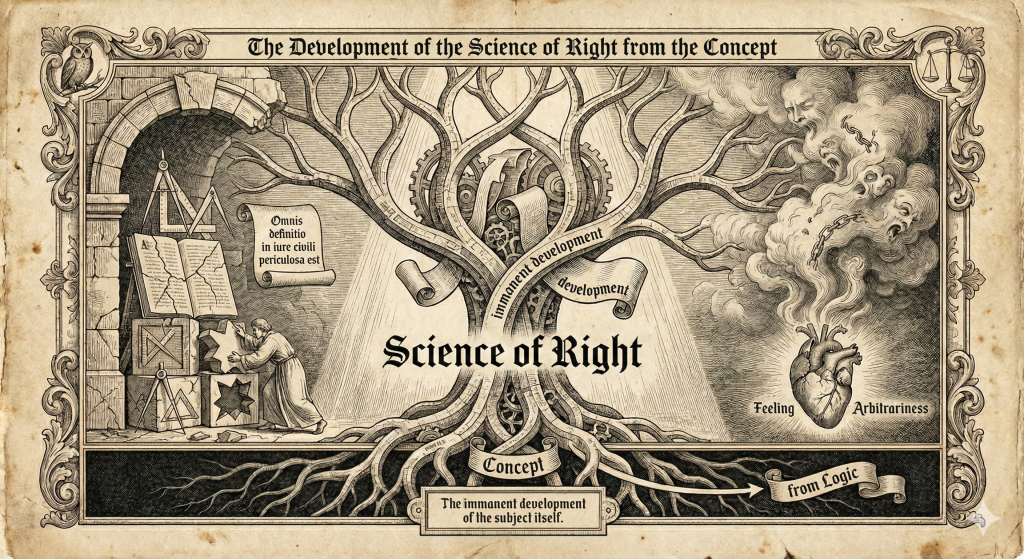

The science of right is a part of philosophy. It has, therefore, to develop the Idea—which is the reason of an object—out of the Concept, or, what is the same thing, to watch its own, immanent development of the matter itself. As a part, it has a determinate starting point, which is the result and the truth of what precedes it and what constitutes its so-called proof. The Concept of Right, in terms of its coming-to-be, therefore falls outside the science of right; its deduction is presupposed here, and it is to be taken up as something given.

According to the formal, non-philosophical method of the sciences, a definition is sought and demanded first of all, at least for the sake of external scientific form. The positive science of law, by the way, cannot be much concerned with this, since its primary aim is to state what is lawful (Rechtens), i.e., what the particular legal provisions are, which is why the warning was issued: omnis definitio in iure civili periculosa (every definition in civil law is perilous). And in fact, the more incoherent and self-contradictory the provisions of a body of law are, the less possible are definitions within it, for definitions are meant to contain universal determinations, and these immediately make the contradictory—in this case, the unjust—visible in its nakedness. Thus, for example, no definition of man would be possible under Roman law, for the slave could not be subsumed under it; in his status, that very concept is violated. Likewise, the definition of property and proprietor would appear perilous for many legal relationships. — The deduction of a definition, however, is derived perhaps from etymology, and especially from abstracting from particular cases, taking the feeling and representation of human beings as its basis. The correctness of the definition is then made to consist in its agreement with existing representations. With this method, that which alone is scientifically essential is set aside: with respect to the content, the necessity of the thing in and for itself (here, of right), and with respect to the form, the nature of the Concept.

In philosophical cognition, by contrast, the necessity of a Concept is the main thing, and the process of its having become a result is its proof and deduction. Since its content is thus necessary in itself, the second step is to look around for what corresponds to it in our representations and in language. But how this Concept is in and for itself in its truth, and how it is in representation, can not only be different from each other, but must be so in form and configuration. If, however, the representation is not also false in its content, the Concept can certainly be shown to be contained within it and, according to its essence, to be present in it; that is, the representation can be elevated to the form of the Concept. But the representation is so far from being the measure and criterion of the Concept that is necessary and true in and for itself that it must, on the contrary, take its truth from the Concept, and be rectified and cognized from it. — If, however, that first way of cognizing with its formalities of definitions, inferences, proofs, and the like has on the one hand more or less disappeared, it has, on the other hand, received a foul substitute in another manner: namely, that of apprehending and asserting Ideas in general, and thus also the Idea of Right and its further determinations, directly as facts of consciousness, and of making natural or intensified feeling, one’s own breast and enthusiasm, the source of right. While this method is the most convenient of all, it is at the same time the most unphilosophical — not to mention here other aspects of this view which relate not merely to cognition but directly to action. While the first, formal method still demands the form of the Concept in the definition and, in the proof, the form of a necessity of cognition, the manner of immediate consciousness and feeling makes the subjectivity, contingency, and arbitrariness of knowledge into a principle. — What the scientific procedure of philosophy consists in is to be presupposed here from philosophical Logic.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.